Though he lived on a typical Southern California cul-de-sac filled with middle-class office workers who commuted into San Diego every day, Adrian’s upbringing stood out for the sense of mission brought by his parents. Money earned by the tae kwon do studios his father ran was largely plowed into the Gloria World Mission, a charity his parents created to help poor and disadvantaged people in Tijuana. The family would frequently make the half-hour drive over the border, spending weekends and religious holidays. The family car had the mission’s name emblazoned on the side. “Let us not live with words or tongue, but with actions and in truth” was the Bible quotation on the website of his father’s studio, which described itself as the “fundraising arm” of the Gloria World Mission. Adrian later told a friend that his parents had raised him with an obsession about getting good grades, but not about what to do after he got them. “I am just a normal dude, went to public school,” he told the friend. “I did well, but when I got to college, I wondered what was the point?” For much of his teenage years and first year at college, Adrian couldn’t quite put his finger on which direction to take his life. Soon after arriving at Yale, he and Nakanishi began attending meetings of the Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán, a social justice group originally established in 1969, where there was vibrant discussion of the U.S. response to 9/11. Nakanishi’s dad was a co-founder of the group as well as the Asian American Students Association decades earlier

چکیده فارسی

اگرچه او در یک بن بست معمولی در کالیفرنیای جنوبی زندگی می کرد که پر از کارکنان اداری طبقه متوسط بود که هر روز به سن دیگو رفت و آمد می کردند، تربیت آدریان به دلیل احساس مأموریتی که والدینش به ارمغان آوردند برجسته بود. پول حاصل از استودیوهای تکواندو که پدرش اداره میکرد تا حد زیادی به ماموریت جهانی گلوریا، موسسه خیریهای که والدینش برای کمک به افراد فقیر و محروم در تیجوانا ایجاد کردند، اختصاص یافت. خانواده غالباً نیم ساعت رانندگی از مرز را طی می کردند، آخر هفته ها و تعطیلات مذهبی را می گذرانند. روی خودروی خانوادگی نام مأموریت در کنار آن نقش بسته بود. نقل قول کتاب مقدس در وبسایت استودیوی پدرش که خود را «بازوی جمعآوری کمک مالی» مأموریت جهانی گلوریا توصیف میکرد، «اجازه دهید با کلمات یا زبان زندگی نکنیم، بلکه با اعمال و حقیقت زندگی کنیم». آدریان بعداً به یکی از دوستانش گفت که والدینش او را با وسواس در مورد گرفتن نمرات خوب بزرگ کرده بودند، اما نه اینکه بعد از گرفتن آنها چه کاری انجام دهد. او به دوستش گفت: "من فقط یک شخص عادی هستم، به مدرسه دولتی رفتم." "من خوب کار کردم، اما وقتی به دانشگاه رسیدم، فکر کردم که چه فایده ای داشت؟" آدریان در بیشتر سالهای نوجوانی و سال اول تحصیلش در کالج، نمیتوانست انگشتش را در کدام مسیر بگذارد تا زندگیاش را بگیرد. بلافاصله پس از ورود به ییل، او و ناکانیشی شروع به شرکت در جلسات Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán کردند، یک گروه عدالت اجتماعی که در ابتدا در سال 1969 تأسیس شد، جایی که بحث های پرشور در مورد واکنش ایالات متحده به 11 سپتامبر وجود داشت. پدر ناکانیشی یکی از بنیانگذاران این گروه و همچنین انجمن دانشجویان آسیایی آمریکایی چندین دهه قبل بود

ادامه ...

بستن ...

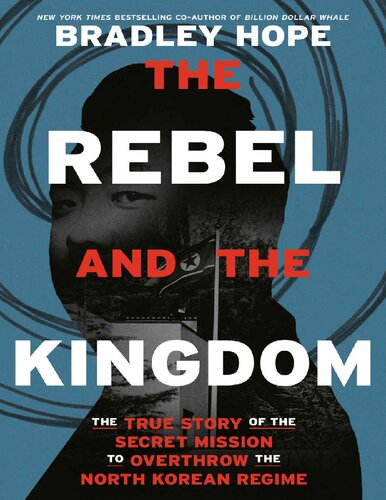

Students discussed what happened to Japanese residents of the United States and Asian Americans after Pearl Harbor. Would that happen now to Muslim Americans? Adrian was a spirited participant. Adrian frequently showed a strong aversion to the status quo, the established wisdom on all topics, and the safe options for a young person making their way in the world. To him, there was a sense of meaning missing from so many efforts around him. On AOL Instant Messenger he communicated under the username “areadymadelife,” the title of a 1934 short story by the Korean novelist Chae Man-sik depicting middle-class Koreans with good educations but no direction. The feeling resonated with Adrian. He saw Korean and Korean American youths adrift without a deeper purpose. As a plucky freshman at Yale, he wrote a sixteen-hundred-word op-ed in The Korea Herald lamenting the decline of values of his brethren and calling for Koreans at home and abroad to stop obsessing over material gains and foster a deeper appreciation of Korean heritage and its history of fighting oppressors. “Where are the college students of old, who rallied for democracy and freedom in the 70s and 80s?” he wrote. “Where are the aware, educated youth that would shake this earth? They have disappeared.” The article describes his personal journey to learn more about Korea and his heritage, including an impromptu trip to the Korean Mission to the United Nations, where he was denied entry. But here he was in January 2002—just eighteen years old, making him one of the younger members of his class—writing a long article about Korea without ever directly mentioning the North. The only references are to the concept of “reunification” and South Korea’s long history of fighting communists. Adrian was still a campaigner in search of a campaign. Then he encountered a book that would change the course of his life

ادامه ...

بستن ...