osa Luxemburg, because they were murdered by those who paved the way for fascism. Although both of them were members of the same party for a long time, fought for socialism, relentlessly spoke out and stood up against the war, and addressed the same problems, the underlying causes and associated perpetrators both in theory and practice, they were unable to cooperate with one another. The fact that Rosa Luxemburg meticu- lously and thoroughly studied Hilferding’s Finance Capital is confirmed by her extensive writings in the form of notes, conspectuses, text and speech drafts (e.g. Luxemburg [1910–1913], p. 152), as well as records and transcripts of her lectures by her students at the SPD’s party school (e.g. Walcher [1910/1911], p. 369). Various letters provide further hints in this regard. Unfortunately, she never actually wrote the review of Finance Capital she had announced to Kostya Zetkin (Luxemburg [1911a] p. 41) and never referred to the book or its analyses in her own publications. In fact, she even suspected the ‘dirt monger Hilferding’ (Luxemburg [1911b], p. 142) of having organised the campaign against her Accumulation of Capital (Luxemburg 1913c, p. 265): ‘Hilf[erding] is behind this’ (Luxemburg 1913a, p. 267), she remarked to Leo Jogiches (see also [Luxemburg 1913b], p. 266). Hilferding, for his part, outwardly ignored Luxemburg’s theoretical and political achievements for decades. According to Leon Trotsky, he must have hated her (Trotsky 1929). It was only in 1920, during a very heated argument with Gregory Zinoviev, that Hilferding paid tribute to Rosa Luxemburg, albeit very selectively (Hilferding 1920, pp. 152ff). Zinoviev—on orders of the Executive Committee of the Communist International—had responded to the USPD’s request for affiliation by informing them of 21 conditions for membership. In sum, he demanded no less than the USPD’s submission, or rather ‘Bolshevisation’. Hilferding based his stance on Luxemburg’s argument put forward against Lenin, who wanted to develop party mem- bers as party soldiers, forging the workers’ party as a centralised organisation. Even though both Luxemburg and Hilferding vehemently rejected Lenin’s party concept and its conception of human beings, this does not mean that they shared a common view on the tasks of the workers’ party and its members. After all, Hilferding considered the parliament to be the most important field of political struggle, and he developed—despite his explicit demand to be open to argument and despite the aptitude for J. DELLHEIM AND F. O. WOLF 3 pragmatism1 he proved to possess during his time as Reich Finance Minister—a peculiar kind of dogmatism. As a result, he turned out, par- ticularly during the crucial years of 1931/1932, to be an opponent of any kind of trade-unionist anti-depression programme because, in his view, government deficit spending contradicted the legitimate boundaries of capitalist economic policy (Stephan 1982, p. 239). Ever since his experience with Bolshevism and its uncritical followers in Germany, Hilferding had begun to include an undifferentiated anti- communist stance among his political principles. Such positions defended by social democrats facilitated the disastrous Stalinist thesis of ‘social fas- cism’, reflecting and reinforcing the historical inability by Social Democrats and Communists to form an anti-fascist alliance. Neither his escape from Germany (Hilferding 1933/1982, pp. 268f, see also Stephan 1982, pp. 279–802) nor the German attack on Poland could convince Hilferding otherwise (Hilferding 1940, p. 290). As early as the 1920s, the indepen- dent leftist and brilliant and sharp-tongued journalist Carl von Ossietzky mocked the irrational anti-communist politics as pursued by leading Social Democrats, particularly by such figures as Rudolf Hilferding in his exclu- sive orientation on parliamentary politics and governmental policies (e.g. Ossietzky 1924/2014, p. 64).

چکیده فارسی

اوزا لوکزامبورگ، زیرا آنها توسط کسانی به قتل رسیدند که راه را برای فاشیسم هموار کردند. اگرچه هر دوی آنها برای مدت طولانی عضو یک حزب بودند، برای سوسیالیسم جنگیدند، بی امان صحبت کردند و در برابر جنگ ایستادند، و به مشکلات یکسانی پرداختند، علل اساسی و عاملان مرتبط، چه در تئوری و چه در عمل، نتوانستند. برای همکاری با یکدیگر این واقعیت که روزا لوکزامبورگ به طور دقیق و کامل سرمایه مالی هیلفردینگ را مطالعه کرد، با نوشتههای گسترده او در قالب یادداشتها، جمعبندیها، پیشنویسهای متن و گفتار (مثلاً لوکزامبورگ [1910-1913]، ص 152)، و همچنین سوابق تأیید میشود. و متن سخنرانی های او توسط دانش آموزانش در مدرسه حزب SPD (به عنوان مثال والچر [1910/1911]، ص 369). نامه های مختلف نکات بیشتری در این زمینه ارائه می دهد. متأسفانه، او هرگز در واقع بررسی سرمایه مالی را که به کوستیا زتکین اعلام کرده بود ننوشت (لوکزامبورگ [1911a] ص 41) و هرگز به کتاب یا تحلیلهای آن در انتشارات خود مراجعه نکرد. در واقع، او حتی به «هیلفردینگ» (لوکزامبورگ [1911b]، ص 142) مشکوک بود که مبارزات انتخاباتی علیه انباشت سرمایه او را سازماندهی کرده است (لوکزامبورگ 1913c، ص 265): «هیلف[erding] پشت این کار است». (لوکزامبورگ 1913 الف، ص 267)، او به لئو جوگیش اشاره کرد (نگاه کنید به [لوکزامبورگ 1913 ب]، ص 266). هیلفردینگ، به نوبه خود، در ظاهر دستاوردهای نظری و سیاسی لوکزامبورگ را برای چندین دهه نادیده گرفت. به گفته لئون تروتسکی، او باید از او متنفر بوده باشد (تروتسکی 1929). تنها در سال 1920 بود که هیلفردینگ در جریان یک مشاجره بسیار شدید با گرگوری زینوویف، به رزا لوکزامبورگ ادای احترام کرد، البته بسیار گزینشی (Hilferding 1920, pp. 152ff). زینوویف - به دستور کمیته اجرایی انترناسیونال کمونیستی - به درخواست USPD برای وابستگی پاسخ داده بود و آنها را از 21 شرط برای عضویت مطلع کرده بود. در مجموع، او چیزی کمتر از تسلیم USPD یا بهتر بگوییم «بلشویزاسیون» را خواستار شد. هیلفردینگ موضع خود را بر اساس استدلال لوکزامبورگ بر ضد لنین استوار کرد که می خواست اعضای حزب را به عنوان سربازان حزب توسعه دهد و حزب کارگران را به عنوان یک سازمان متمرکز بسازد. اگرچه لوکزامبورگ و هیلفردینگ به شدت مفهوم حزب لنین و تصور آن از انسان را رد کردند، این بدان معنا نیست که آنها دیدگاه مشترکی در مورد وظایف حزب کارگر و اعضای آن داشتند. از این گذشته، هیلفردینگ پارلمان را مهمترین میدان مبارزه سیاسی میدانست و توسعه مییابد - علیرغم تقاضای صریح خود برای بحثپذیری و علیرغم استعداد عملگرایی J. DELLHEIM و F. O. WOLF 3 که در طول زمان خود ثابت کرد که از آن برخوردار است. به عنوان وزیر دارایی رایش - نوعی جزم گرایی عجیب. در نتیجه، مشخص شد که او بهویژه در سالهای سرنوشتساز 1931/1932، مخالف هر نوع برنامه اتحادیهای ضد افسردگی بود، زیرا از نظر او، مخارج کسری دولت با مرزهای قانونی سرمایهداری در تضاد بود. سیاست اقتصادی (استفان 1982، ص 239). هیلفردینگ از زمان تجربه اش با بلشویسم و پیروان غیرانتقادی آن در آلمان، شروع به گنجاندن یک موضع ضد کمونیستی تمایز ناپذیر در میان اصول سیاسی خود کرده بود. چنین مواضعی که توسط سوسیال دموکراتها دفاع میشد، تز فاجعهبار استالینیستی «سوسیال فاشیسم» را تسهیل کرد و ناتوانی تاریخی سوسیال دموکراتها و کمونیستها برای تشکیل یک اتحاد ضدفاشیستی را منعکس و تقویت کرد. نه فرار او از آلمان (هیلفردینگ 1933/1982، ص 268f، همچنین نگاه کنید به استفان 1982، صفحات 279-802) و نه حمله آلمان به لهستان نتوانست هیلفردینگ را در غیر این صورت متقاعد کند (هیلفردینگ 1940، ص 290). در اوایل دهه 1920، کارل فون اوسیتسکی، روزنامهنگار مستقل، چپگرا و باهوش و تیزبین، سیاست غیرمنطقی ضد کمونیستی را که توسط سوسیال دموکراتهای پیشرو، بهویژه چهرههایی مانند رودولف هیلفردینگ در جهتگیری انحصاری خود در پارلمان دنبال میشد، به سخره گرفت. سیاست و سیاست های دولتی (به عنوان مثال، Ossietzky 1924/2014، ص 64).

ادامه ...

بستن ...

ISSN 2662-6373 ISSN 2662-6381 (electronic)

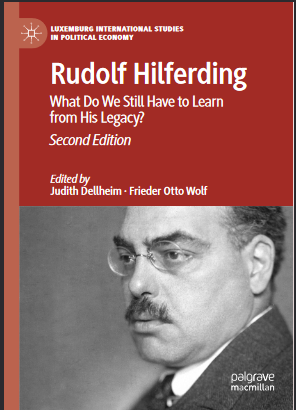

Luxemburg International Studies in Political Economy

ISBN 978-3-031-08095-1 ISBN 978-3-031-08096-8 (eBook)

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08096-8

© The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer

Nature Switzerland AG 2023, 2020

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the

Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of

translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on

microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval,

electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now

known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this

publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are

exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors, and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information

in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the

publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to

the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The

publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and

institutional affiliations.

Cover illustration: Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe

This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature

Switzerland AG.

The registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland

ادامه ...

بستن ...