Tuesday, July 14, 2009, was a good day.

I opened my apartment door around seven a.m. to find my Wall Street Journal delivered, with my byline in it. My two-year-old son, Jasper, woke up around the same time. We played with puzzles and had breakfast before I put him in the stroller at eight and walked in the easy sunshine to his preschool two blocks away. I spent the next 4 hours writing. Then I logged 45 minutes on the stationary bike, reading a book I needed to review to make the most of that time. After, I wrote for 3 more hours. I packed snacks for Jasper and picked him up shortly after four p.m., intending to take him to an exhibit I’d read about at the Museum of Modern Art. Alas, the museum was closed, as it is every Tuesday, so we had to regroup, buy a pretzel from a street vendor, and admire the more realist “art” of the Fifth Avenue bustle. At least during the expedition we found the new pair of sneakers he’d needed. We got home at 5:30 and played until the babysitter came an hour later. Then I zoomed out to Brooklyn to run a long-range planning meeting for the Young New Yorkers’ Chorus, for which I serve as president. My board talked about how to commission new music, how to improve our musical craft, and how to make people feel at home in this grand city. I zipped home and spent 45 minutes talking with my husband, Michael, about our projects and potential names for the second son we were expecting in two months. It was roughly a 17-hour day by the time I went to sleep, with 8 spent working (0.75 of those also spent exercising), 4 spent interacting with family, 3 spent on my volunteer work, and a few transitions and other things in between. It was a busy day, devoid of disasters, though devoid of spectacular triumphs, too. So why was it “good”?

Much has been written about the good life—what it means to be happy or successful, in our own minds at least, and how people become that way. I am as much a student of these books as anyone else, and I have always been drawn to the stories of people who love what they do, who live full lives and have grand aspirations. As a journalist, I have interviewed many such people, and I often daydream about what I’d like to get out of life as well.

Over the years, those daydreams have taken on some shape and substance. Since I was a child I’ve wanted to be a writer. I also wanted to be a mom. Growing up near the cornfields of Indiana, I wanted to live in a big city for at least a while when I was young enough not to mind the grit and noise. I love music, and I love to help create new things, be they songs or books. I love having health and energy. But all these things are abstractions. All are ideas people think about in phrases such as “when I grow up” or “someday,” or broadly as our identities and values.

A few years ago, though, I had a realization: while we think of our lives in grand abstractions, a life is actually lived in hours. If you want to be a writer, you must dedicate hours to putting words on a page. To be a mindful parent, you must spend time with your child, teaching him that even though he loves the new shoes he picked out, he has to take them off so mommy can pay for them. A solid marriage requires conversation and intimacy and a focus on family projects. If you want to sing well in a functioning chorus, you must show up to rehearsals and practice on your own in addition to setting goals and attending to any administrative duties. If you want to be healthy, you must exercise and get enough sleep. In short, if you want to do something or become something—and you want to do it well—it takes time.

What made that particular Tuesday a good day was the high proportion of hours I spent on things that relate to my life goals. For instance, I wanted to be a writer, and I am. That is what I spent big chunks of my time doing.

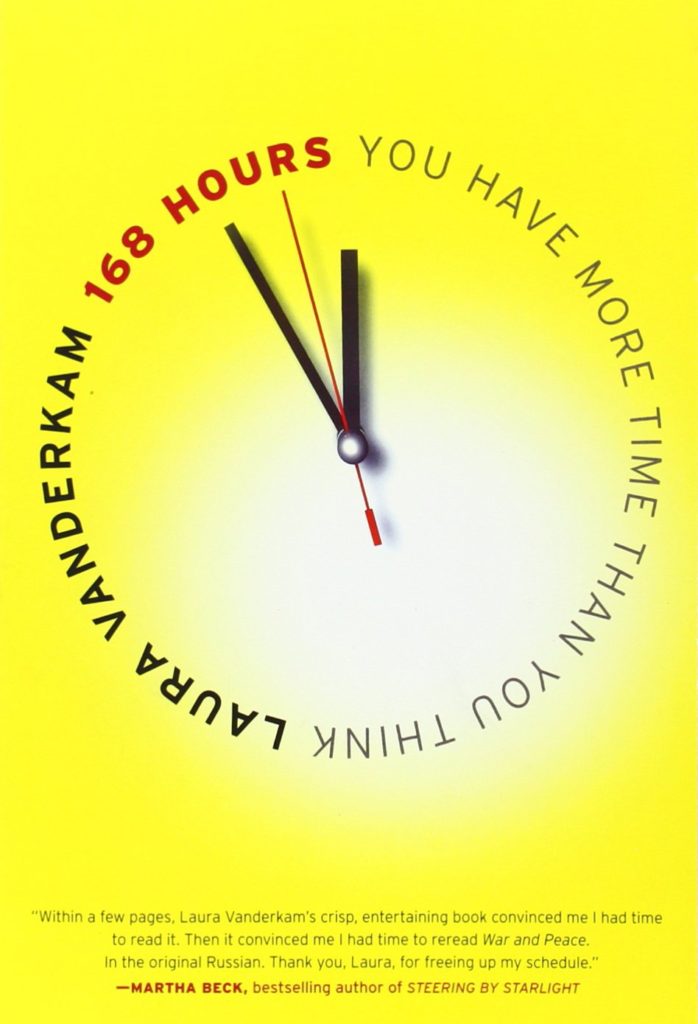

July 14 was, of course, a 24-hour day, and this is the way most of us are accustomed to thinking about our time: as 24-hour blocks. But as I’ve pondered the question of how I want to live my life, I’ve come to believe that it’s more useful to think in terms of “24/7,” a phrase people toss about but seldom multiply through. There are 168 hours in a week. My busy Tuesday was a good day, but so was my slower Sunday spent going to church, walking for 2 hours in Central Park, and—yes—working for 4 hours during Jasper’s nap and after he went to bed. The way I see it, anything you do once a week happens often enough to be important to you, whether it’s church, a strategic thinking session at work, your Sunday dinner with your parents, or your softball team practice. The weekly 168-hour cycle is big enough to give a true picture of our lives. Years and decades are made up of a mosaic of repeating patterns of 168 hours. Yes, there is room for randomness, and the mosaic will evolve over time, but whether you pay attention to the pattern is still a choice. Largely, the true picture of our lives will be a function of how we set the tiles. This book is about how different people spend the 168 hours we all have per week. It is about where the time really goes, and how we can all use our time better. It is about using our hours to focus on what we do best in our careers and at home, and so take a life’s work to the next level while investing in our personal lives as well. I wanted to write this book for several reasons. For starters, despite the ongoing cultural narrative of a time crunch—a narrative often aimed at women like me, a working mom of small kids—I don’t feel like I’m forever falling behind. I’d be the first to admit that my life is inordinately privileged, something I am sure some folks reading this book will delight in pointing out. But I know that I’m not the only one who feels this way. Some of the busiest, most successful people I’ve ever interviewed have told me that they could cram more into their lives if they wished. Looking at life in 168-hour blocks is a useful paradigm shift, because—unlike the occasionally crunched weekday—well-planned blocks of 168 hours are big enough to accommodate full-time work, intense involvement with your family, rejuvenating leisure time, adequate sleep, and everything else that actually matters. Of course, there is also a political element in this portrait of time. I have written this book for men and women. It is for parents, nonparents, and people who never want to be parents. It is for people with all sorts of goals, careers, and interests. Still, I am particularly alarmed by how many of the brightest young women of my generation do not believe they can possibly weave together a Career with a capital C, motherhood, and a personal life in the hours the universe allots them without feeling frazzled, sleep�deprived, and pulled in ten directions at once. From time to time, pundits and bloggers set themselves howling over surveys that seem to show this. In September 2005, Louise Story announced on the front page of The New York Times that many female Yale undergrads planned to cut back on work or stop working entirely after becoming mothers. As she quoted one student, “My mother always told me that you can’t be the best career woman and the best mother at the same time.” The implication? You have to choose. Likewise, the Princeton University student Amy Sennett polled fellow members of the class of 2006 for her senior thesis and found that women were still quite likely to believe that “being a successful career woman and being a good mother are mutually exclusive.” Some 62 percent of women saw a potential conflict between career and childrearing; only 33 percent of men did. Of those women who saw a conflict, the majority planned to work part-time, and another high proportion planned to “sequence”—that is, take a few years off and then return to the workforce. A few young women did think combining a career and motherhood was possible, but they had stark ideas of other things that would have to go. As one history major told Sennett, “I plan never to sleep.” These dire predictions were certainly in the back of my mind when I decided to do something unusual for the Ivy League urban professional set and get pregnant for the first time at age twenty-seven. I won’t pretend that becoming a mother has been entirely rosy, or that my household is a scene of domestic bliss. However, motherhood did not ruin my career, and my work has not detracted from how much I love being a mom, particularly the small moments of seeing another human being figure out the world—small moments the universe grants in abundance when you choose to pay attention. If anything, the combination of work and motherhood has given me more things to write about. One of those things has been time use. Not long after I came back from whatever you call maternity leave when you’re self-employed, I discovered the American Time Use Survey and fascinating research from the University of Maryland and elsewhere about how people—moms and dads in particular— actually spend their time. I began writing about these findings in my columns for USA Today , in a nine�part series for The Huf ington Post about “Core Competency Moms,” in features for Doublethink and the now-defunct Culture 11, in essays for the Taste page of The Wall Street Journal , and as a guest writer for Lisa Belkin’s “Motherlode” blog at The New York Times. The more I studied time use and talked to people who do amazing things with their lives, the more I came to see that this bleak notion of mutual exclusivity between work and family is based on misleading ideas of how people spend their family time now, and how they spent it in the past. On the flipside, I do want to demystify “work” a little, too. I put “work” in quotes here because, after studying how people spend their time, I believe that certain widespread (and self-important) assumptions about the way we work today are just as misplaced as our assumptions about how people lived in the 1950s: we assume we are all overworked, just as we assume everyone used to live like Ozzie and Harriet. In reality, neither of these perceptions is true. The majority of people who claim to be overworked work less than they think they do, and many of the ways people work are extraordinarily inefficient. Calling something “work” does not make it important or necessary. One of my missions in this book is to make people look at their time in all spheres of life and say “I hadn’t thought of it that way before.” There are other ways in which 168 Hours does not aim to be like many self-help or time-management books. I approach this not as a productivity guru, but as a journalist who is interested in how successful, happy people build their lives. I am particularly interested in how people who are not household names achieve the lives they want, and what we can learn from their best practices. There are plenty of books out there on Fortune 500 CEOs’ or celebrities’ tips for success. I’m more interested in the woman down the street who—without benefit of fame, outsized fortune, or a slew of personal assistants—is running a successful small business, marathons, and a large and happy household. As a corollary to that, real life is often messy, but I don’t believe there’s much value in tales of composite characters that I made up just to show that my methods worked. Everyone in this book is real, with their real names and real stories. I find footnotes distracting, but the endnotes provide backup for the facts or studies cited. While I’ve put interactive material at the ends of most chapters, I can’t promise 5- minute tweaks that will completely change your life. Certainly, everyone’s life can benefit from quick tune-ups, but getting the most out of your 168 hours takes discipline in a distracted world. Reading fiction as you commute to a job you don’t like will make you feel somewhat more fulfilled; being in the right job will make you feel incredible. Going for a 10-minute walk will lift your spirits; committing to run for 4 of every 168 hours for the next year will transform your health. Finally, 168 Hours is unlike many business- and life-management books in that—while I appear in the narrative—I can’t claim to be writing from a position of authority as a great success story. I am not writing this book to impart a lifetime of learned wisdom. I wrote the bulk of this manuscript when I was thirty years old. My life is definitely a work in progress. I don’t think I’m doing a bad job fitting the pieces together. Nonetheless, I have learned a lot during the process. I have tried to implement these findings in my own plans; 168 Hours is, at least in part, about that journey of trying to have more good Tuesdays. And Mondays. And Saturdays. And all the other days that make up the 168-hour mosaic of our lives .

چکیده فارسی

سه شنبه، 14 جولای 2009، روز خوبی بود.

حدود هفت صبح در آپارتمانم را باز کردم تا وال استریت ژورنال تحویل داده شده را پیدا کنم که خط نوشته ام در آن است. پسر دو ساله من، جاسپر، در همان زمان از خواب بیدار شد. با پازل بازی کردیم و صبحانه خوردیم قبل از اینکه ساعت هشت او را در کالسکه بگذارم و در زیر نور آفتاب آسان به پیش دبستانی اش در دو بلوک راه رفتم. من 4 ساعت بعد را صرف نوشتن کردم. سپس 45 دقیقه سوار دوچرخه ثابت شدم و کتابی را خواندم که باید مرور کنم تا از آن زمان بهترین استفاده را ببرم. بعدش 3 ساعت دیگه نوشتم. من برای جاسپر تنقلات تهیه کردم و کمی بعد از ساعت چهار بعد از ظهر او را برداشتم و قصد داشتم او را به نمایشگاهی ببرم که در موزه هنر مدرن درباره آن خوانده بودم. افسوس، موزه مانند هر سهشنبه تعطیل بود، بنابراین مجبور شدیم دوباره جمع شویم، از یک فروشنده خیابانی یک چوب شور بخریم و «هنر» واقعگرایانهتر شلوغی خیابان پنجم را تحسین کنیم. حداقل در طول سفر ما جفت کفش ورزشی جدیدی را که او نیاز داشت پیدا کردیم. ساعت 5:30 به خانه رسیدیم و بازی کردیم تا یک ساعت بعد پرستار بچه آمد. سپس به بروکلین زوم کردم تا یک جلسه برنامه ریزی بلندمدت برای گروه کر جوان نیویورکی برگزار کنم، که من به عنوان رئیس آن خدمت می کنم. هیئت مدیره من در مورد چگونگی سفارش موسیقی جدید، چگونگی بهبود هنر موسیقی و اینکه چگونه مردم در این شهر بزرگ احساس کنند که در خانه هستند صحبت کردند. من به خانه رفتم و 45 دقیقه با شوهرم، مایکل، درباره پروژههایمان و نامهای احتمالی پسر دومی که در دو ماه آینده انتظار داشتیم صحبت کردم. تقریباً یک روز 17 ساعتی بود که من به خواب رفتم، 8 نفر از آنها کار کردند (0.75 نفر از آنها نیز ورزش کردند)، 4 نفر در تعامل با خانواده، 3 ساعت صرف کار داوطلبانه من، و چند تغییر و چیزهای دیگر در بین. روز شلوغی بود، عاری از فاجعه، اگرچه عاری از پیروزی های دیدنی نیز بود. پس چرا "خوب" بود؟

درباره زندگی خوب بسیار نوشته شده است - حداقل در ذهن خود ما شاد بودن یا موفق بودن به چه معناست، و اینکه چگونه مردم چنین می شوند. من به اندازه هر کس دیگری دانشآموز این کتابها هستم، و همیشه به سمت داستانهای افرادی کشیده شدهام که عاشق کاری هستند که انجام میدهند، زندگی کاملی دارند و آرزوهای بزرگی دارند. بهعنوان یک روزنامهنگار، با بسیاری از افراد این چنینی مصاحبه کردهام، و اغلب درباره آنچه که میخواهم از زندگی به دست بیاورم، خیالپردازی میکنم.

در طول سالها، آن رویاهای روزانه شکل و ماهیتی به خود گرفته است. از کودکی دوست داشتم نویسنده شوم. من هم می خواستم مامان شوم. وقتی در نزدیکی مزارع ذرت ایندیانا بزرگ شدم، میخواستم حداقل برای مدتی در یک شهر بزرگ زندگی کنم، زمانی که به اندازه کافی جوان بودم و به شن و ماسه و سر و صدا اهمیت نمیدادم. من عاشق موسیقی هستم و دوست دارم به خلق چیزهای جدید کمک کنم، چه آهنگ و چه کتاب. من عاشق داشتن سلامتی و انرژی هستم. اما همه این چیزها انتزاعی هستند. همه ایده هایی هستند که مردم در عباراتی مانند "وقتی بزرگ شدم" یا "روزی" یا به طور کلی به عنوان هویت و ارزش های ما به آنها فکر می کنند.

چند سال پیش، با این حال، متوجه شدم: در حالی که ما به زندگی خود به صورت انتزاعی بزرگ فکر می کنیم، یک زندگی در واقع در چند ساعت زندگی می شود. اگر می خواهید نویسنده شوید، باید ساعت ها را به قرار دادن کلمات در صفحه اختصاص دهید. برای اینکه والدینی آگاه باشید، باید زمانی را با فرزندتان بگذرانید و به او بیاموزید که با وجود اینکه عاشق کفش های جدیدی است که انتخاب کرده است، باید آن ها را در بیاورد تا مادر بتواند هزینه آن را بپردازد. ازدواج مستحکم مستلزم گفتگو و صمیمیت و تمرکز بر پروژه های خانوادگی است. اگر میخواهید در یک گروه کر کارآمد آواز بخوانید، باید علاوه بر تعیین اهداف و انجام هر گونه وظایف اداری، در تمرینها حاضر شوید و به تنهایی تمرین کنید. اگر می خواهید سالم باشید، باید ورزش کنید و به اندازه کافی بخوابید. به طور خلاصه، اگر میخواهید کاری را انجام دهید یا چیزی شوید—و میخواهید آن را به خوبی انجام دهید—زمان میبرد.

آنچه آن سه شنبه خاص را به روز خوبی تبدیل کرد، نسبت بالای ساعاتی بود که صرف کارهایی می کردم که به اهداف زندگی ام مربوط می شود. به عنوان مثال، من می خواستم نویسنده شوم و هستم. این همان چیزی است که من بخش زیادی از وقتم را صرف انجام آن کردم.

14 ژوئیه، البته، یک روز 24 ساعته بود، و این روشی است که اکثر ما عادت داریم به زمان خود فکر کنیم: به عنوان بلوک های 24 ساعته. اما وقتی به این سوال فکر میکردم که چگونه میخواهم زندگیام را بگذرانم، به این باور رسیدهام که فکر کردن در قالب «24 ساعته» مفیدتر است، عبارتی که مردم آن را پرتاب میکنند اما به ندرت آن را تکرار میکنند. 168 ساعت در هفته وجود دارد. سهشنبه شلوغ من روز خوبی بود، اما یکشنبه آهستهتر من هم برای رفتن به کلیسا، ۲ ساعت پیادهروی در پارک مرکزی، و - بله - کار کردن به مدت ۴ ساعت در طول چرت جاسپر و بعد از اینکه او به رختخواب رفت. آن طور که من می بینم، هر کاری که هفته ای یک بار انجام می دهید، اغلب آنقدر اتفاق می افتد که برایتان مهم باشد، خواه کلیسا، یک جلسه تفکر استراتژیک در محل کار، شام یکشنبه با والدینتان، یا تمرین تیم سافت بال شما. چرخه 168 ساعته هفتگی آنقدر بزرگ است که تصویری واقعی از زندگی ما ارائه دهد. سال ها و دهه ها از موزاییکی از الگوهای تکراری 168 ساعته تشکیل شده اند. بله، جایی برای تصادفی بودن وجود دارد، و موزاییک در طول زمان تکامل مییابد، اما اینکه آیا به الگوی آن توجه کنید هنوز یک انتخاب است. تا حد زیادی، تصویر واقعی زندگی ما تابعی از نحوه چیدمان کاشی ها خواهد بود. این کتاب درباره نحوه گذراندن 168 ساعتی که همه ما در هفته داریم توسط افراد مختلف است. این در مورد این است که زمان واقعاً به کجا می گذرد، و چگونه همه ما می توانیم از زمان خود بهتر استفاده کنیم. این در مورد استفاده از ساعات خود برای تمرکز بر آنچه در شغل و خانه خود بهترین انجام می دهیم است، و بنابراین کار یک زندگی را به سطح بالاتری ببریم و در زندگی شخصی خود نیز سرمایه گذاری کنیم. به چند دلیل می خواستم این کتاب را بنویسم. برای شروع، علیرغم روایت فرهنگی مداوم از یک تنگنای زمان - روایتی که اغلب زنانی مانند من را هدف قرار می دهد، مادری شاغل بچه های کوچک - من احساس نمی کنم برای همیشه عقب مانده ام. من اولین کسی خواهم بود که اعتراف می کنم که زندگی من بی اندازه ممتاز است، چیزی که مطمئنم برخی از افرادی که این کتاب را می خوانند از اشاره به آن لذت خواهند برد. اما می دانم که من تنها کسی نیستم که چنین احساسی دارد. برخی از شلوغ ترین و موفق ترین افرادی که تا به حال با آنها مصاحبه کرده ام به من گفته اند که اگر بخواهند می توانند بیشتر وارد زندگی خود شوند. نگاه کردن به زندگی در بلوک های 168 ساعته یک تغییر پارادایم مفید است، زیرا - بر خلاف روزهای هفته که گهگاهی به هم می ریزد - بلوک های 168 ساعته که به خوبی برنامه ریزی شده اند به اندازه کافی بزرگ هستند تا بتوانند کار تمام وقت، مشارکت شدید با خانواده، احیا کننده اوقات فراغت و کافی را داشته باشند. خواب، و هر چیز دیگری که واقعا مهم است. البته در این پرتره زمان یک عنصر سیاسی هم وجود دارد. من این کتاب را برای مردان و زنان نوشته ام. این برای والدین، غیر والدین و افرادی است که هرگز نمی خواهند والدین شوند. این برای افرادی با انواع اهداف، مشاغل و علایق است. با این حال، من به ویژه از این که چگونه بسیاری از باهوش ترین زنان جوان نسل من باور ندارند که می توانند در ساعاتی که کائنات به آنها اختصاص می دهد، شغلی با C بزرگ، مادری، و زندگی شخصی به هم ببافند، بدون احساس گیجی و خوابیدن نگران هستم. محروم شد و یکباره به ده جهت کشیده شد. گاه به گاه، صاحب نظران و وبلاگ نویسان در مورد نظرسنجی هایی که به نظر می رسد این را نشان می دهد، زوزه می کشند. در سپتامبر 2005، لوئیز استوری در صفحه اول نیویورک تایمز اعلام کرد که بسیاری از دانشآموزان زن در دانشگاه ییل قصد دارند پس از مادر شدن، کار خود را کاهش دهند یا به طور کامل کار را متوقف کنند. همانطور که او به نقل از یکی از دانشآموزان گفت: «مادر من همیشه به من میگفت که تو نمیتوانی همزمان بهترین زن حرفهای و بهترین مادر باشی». مفهوم؟ شما باید انتخاب کنید. به همین ترتیب، امی سنت، دانشجوی دانشگاه پرینستون، از اعضای کلاس سال 2006 برای پایان نامه ارشد خود نظرسنجی کرد و دریافت که زنان هنوز کاملاً معتقدند که "یک زن حرفه ای موفق و یک مادر خوب بودن متقابل هستند." حدود 62 درصد از زنان تعارض بالقوه بین شغل و فرزندآوری را دیدند. فقط 33 درصد از مردان این کار را انجام دادند. از بین آن دسته از زنانی که شاهد تعارض بودند، اکثریت برنامه ریزی کردند تا به صورت پاره وقت کار کنند، و بخش بالایی از آن ها برنامه ریزی کردند تا «توالی» کنند - یعنی چند سال مرخصی بگیرند و سپس به نیروی کار بازگردند. چند زن جوان فکر میکردند که ترکیب شغل و مادر شدن ممکن است، اما آنها ایدههای روشنی درباره چیزهای دیگری داشتند که باید از بین بروند. همانطور که یکی از بزرگان تاریخ به سنت گفت: "من قصد دارم هرگز نخوابم." این پیشبینیهای وحشتناک مطمئناً در پس ذهن من بود زمانی که تصمیم گرفتم برای مجموعه حرفهای Ivy League شهری انجام دهم و برای اولین بار در سن بیست و هفت سالگی باردار شوم. وانمود نمیکنم که مادر شدن کاملاً زیبا بوده است، یا اینکه خانه من صحنه خوشبختی خانگی است. با این حال، مادر شدن شغل من را خراب نکرد، و کار من از میزان دوست داشتن مادر بودنم کم نکرده است، به ویژه لحظات کوچک دیدن انسان دیگری که دنیا را کشف می کند - لحظات کوچکی که کیهان به وفور به شما هدیه می دهد. توجه در هر صورت، ترکیب کار و مادری چیزهای بیشتری برای نوشتن به من داده است. یکی از آن چیزها استفاده از زمان بوده است. مدت زیادی بعد از بازگشت از مرخصی زایمان که شما آن را خوداشتغالی مینامید، برگشتم، بررسی استفاده از زمان آمریکا و تحقیقات جالبی را از دانشگاه مریلند و جاهای دیگر در مورد نحوه خرج کردن مردم - به ویژه مادران و پدران - کشف کردم. زمان. من شروع به نوشتن در مورد این یافتهها در ستونهایم برای USA Today کردم، در یک سری نه قسمتی برای The Huf ington Post درباره «مادران شایستگی اصلی»، در ویژگیهای Doublethink و فرهنگ اکنون منقرض شده 11، در مقالههایی برای صفحه سلیقه وال استریت ژورنال، و به عنوان نویسنده مهمان برای وبلاگ "Motherlode" لیزا بلکین در نیویورک تایمز. هر چه بیشتر استفاده از زمان را مطالعه کردم و با افرادی که کارهای شگفت انگیزی را با زندگی خود انجام می دهند صحبت کردم، بیشتر متوجه شدم که این تصور تیره و تار از انحصار متقابل بین کار و خانواده بر اساس ایده های گمراه کننده ای است که مردم اکنون زمان خانواده خود را چگونه می گذرانند. چگونه آن را در گذشته خرج می کردند. از طرف دیگر، من هم میخواهم کمی از «کار» راز زدایی کنم. من "کار" را در اینجا در نقل قول قرار دادم زیرا، پس از مطالعه نحوه گذراندن زمان مردم، معتقدم برخی از فرضیات گسترده (و خود مهم) در مورد نحوه کار ما امروز به همان اندازه که فرضیات ما در مورد نحوه زندگی مردم در دهه 1950 نادرست است. : ما فرض می کنیم همه ما بیش از حد کار کرده ایم، همانطور که فرض می کنیم همه قبلاً مانند اوزی و هریت زندگی می کردند. در واقع، هیچ یک از این تصورات درست نیست. اکثر افرادی که ادعا می کنند بیش از حد کار می کنند، کمتر از آنچه فکر می کنند کار می کنند، و بسیاری از روش های کار افراد فوق العاده ناکارآمد هستند. "کار" نامیدن چیزی آن را مهم یا ضروری نمی کند. یکی از ماموریتهای من در این کتاب این است که مردم را وادار کنم به زمان خود در تمام زمینههای زندگی نگاه کنند و بگویند: «تا به حال اینطور به آن فکر نکرده بودم». راههای دیگری وجود دارد که هدف ۱۶۸ ساعت این نیست که مانند بسیاری از کتابهای خودیاری یا مدیریت زمان باشد. من به این موضوع نه بهعنوان یک مربی بهرهوری، بلکه بهعنوان روزنامهنگاری که علاقهمند است به این موضوع که افراد موفق و شاد چگونه زندگی خود را میسازند، برخورد میکنم. من به ویژه به این موضوع علاقه مند هستم که افرادی که نام خانوادگی ندارند چگونه به زندگی مورد نظر خود دست می یابند و ما می توانیم از بهترین شیوه های آنها چه بیاموزیم. کتابهای زیادی در مورد نکات موفقیت مدیران ارشد یا افراد مشهور در فهرست Fortune 500 وجود دارد. من بیشتر به زنی در خیابان علاقه دارم که - بدون شهرت، ثروت بزرگ یا تعداد زیادی دستیار شخصی - یک تجارت کوچک موفق، ماراتن ها و یک خانواده بزرگ و شاد را اداره می کند. به عنوان نتیجه، زندگی واقعی اغلب درهم و برهم است، اما من فکر نمیکنم داستانهای شخصیتهای ترکیبی که من فقط برای نشان دادن کارآمدی روشهایم ساختهام، ارزش زیادی داشته باشد. همه افراد در این کتاب با نام های واقعی و داستان های واقعی خود واقعی هستند. به نظر من پاورقیها حواسپرتی را ایجاد میکنند، اما یادداشتهای پایانی پشتیبانهایی برای حقایق یا مطالعات ذکر شده ارائه میکنند. در حالی که من مطالب تعاملی را در انتهای اکثر فصل ها قرار داده ام، نمی توانم قول تغییرات 5 دقیقه ای را بدهم که زندگی شما را کاملاً تغییر دهد. مطمئناً، زندگی هر کسی میتواند از تنظیمهای سریع سود ببرد، اما بهرهگیری حداکثری از ۱۶۸ ساعت شما در دنیای پریشان نظم و انضباط میطلبد. خواندن داستان های تخیلی در حین رفت و آمد به شغلی که دوست ندارید باعث می شود تا حدودی احساس رضایت بیشتری کنید. قرار گرفتن در شغل مناسب به شما احساس باورنکردنی می دهد. 10 دقیقه پیاده روی روحیه شما را بالا می برد. متعهد شدن به دویدن 4 ساعت از هر 168 ساعت برای سال آینده سلامت شما را متحول می کند. در نهایت، 168 ساعت برخلاف بسیاری از کتابهای مدیریت زندگی و کسبوکار از این نظر - در حالی که من در روایت ظاهر میشوم- نمیتوانم ادعا کنم که از موقعیتی معتبر به عنوان یک داستان موفقیت بزرگ مینویسم. من این کتاب را نمی نویسم تا یک عمر خرد آموخته را به دیگران منتقل کنم. من بخش عمده این نسخه خطی را در سی سالگی نوشتم. زندگی من قطعاً یک کار در حال پیشرفت است. فکر نمیکنم کار بدی در کنار هم قرار دادن قطعات انجام دهم. با این حال، من در طول این فرآیند چیزهای زیادی یاد گرفتم. من سعی کرده ام این یافته ها را در برنامه های خودم پیاده کنم. 168 ساعت، حداقل تا حدودی، مربوط به آن سفری است که سعی در داشتن سه شنبه های خوب بیشتر دارد. و دوشنبه ها و شنبه ها و همه روزهای دیگری که موزاییک 168 ساعته زندگی ما را تشکیل می دهند.

ادامه ...

بستن ...

PORTFOLIO

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty ) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England First published in 2010 by Portfolio, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copy right © Laura Vanderkam, 2010 All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Vanderkam, Laura. 1

68 hours : y ou have more time than y ou think / Laura Vanderkam. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN : 978-1-101-43294-5 1. Time management. I. Title. II. Title: One hundred sixty -eight hours. HD69.T54V36 2010 658.4’093—dc22 2009046867

ادامه ...

بستن ...